A Better Billion and the Cost Model versus the 125th Street Subway Extension

We released a new report called A Better Billion. It was covered rather positively in the New York Times yesterday, with quotes from other transit advocacy groups. The idea for our report is that Zohran Mamdani promised free buses in his successful primary campaign, and promised free and fast buses in his successful general election campaign for mayor, so let’s take the $1 billion a year this could cost in forgone revenue and see how to spend it on subway expansion instead.

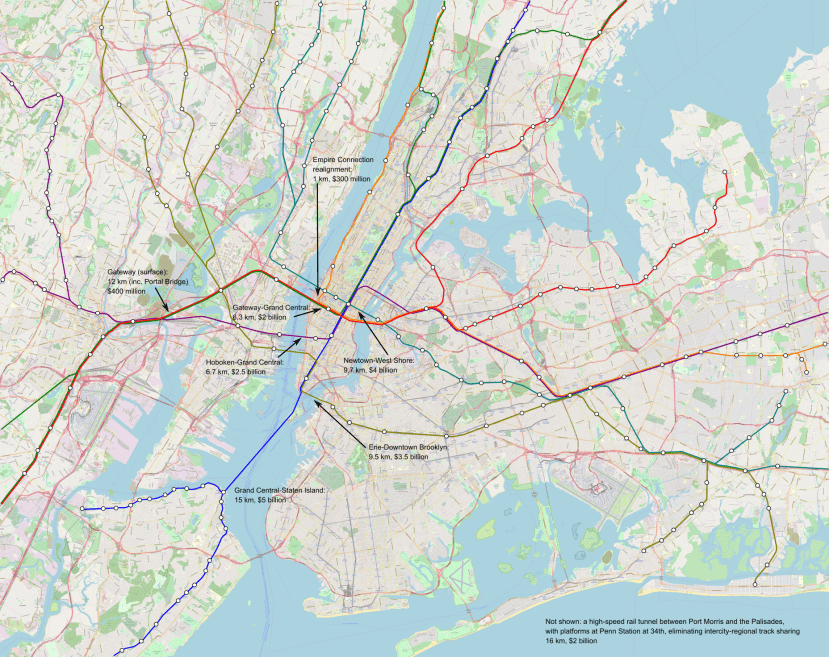

There’s been a lot of discussion in the article and on social media about the idea of free buses, but instead I want to talk about our proposal’s cost model, in the context of a rather incompetent plan the MTA released recently for a subway extension of Second Avenue Subway under 125th Street, at twice the per-km cost of Second Avenue Subway Phases 1 and 2, and twice the cost we project. Our model is not based on non-Anglo costs, but rather on real New York costs, modified to incorporate the one major cost saving coming from our previous reports, namely, shrinking station size. Based on everything combined, we came up with the following medium cost model:

| Item | Cost (2025 prices) |

| Tunnel (1 km) | $530 million |

| Tunnel, underwater (1 km) | $1,050 million |

| El or trench (1 km) | $260 million |

| Station, cut-and-cover | $510 million |

| Station, mined | $770 million |

| Station, el or trench | $240 million |

These costs include apportioned soft costs and not just hard costs. Altogether, an extension of Second Avenue Subway from Park Avenue to Broadway, a distance of 2 km with three mined stations at the intersections with the north-south subway lines, should cost $3.4 billion. This is not much less per kilometer than Second Avenue Subway Phases 1 and 2, which can be explained by the denser stop spacing and the need for mined stations at the undercrossings. If everything else were done in the right way rather than the American way, the low cost model would apply and costs would be reduced further by a factor of about 3, but the per-km cost would remain one of the highest outside the Anglosphere for those geotechnical reasons.

But the MTA and its consultants, in this case AECOM, project $7.7 billion, not $3.4 billion. Why?

Worse project delivery

We’ve assumed the existing project delivery systems the MTA is familiar with. However, what doesn’t move forward moves backward, and the procurement strategy at the MTA is moving backward rapidly, for which the primary culprit is Janno Lieber, first in his role at MTA Capital Construction (now Construction and Development), and then in his role as MTA head, pushing alternative delivery methods, especially design-build and increasingly progressive design-build (unfortunately legalized in New York last year). Such methods add to the procurement costs and especially to the soft costs. Second Avenue Subway Phase 1 had an overall soft cost multiplier of about 1.5: the total cost including soft costs was 1.5 times the hard costs (Italy: 1.2-1.25 times). This proposal, in contrast, has a multiplier of 1.75: the hard costs are estimated at $4.4 billion, and the total costs are 75% higher, technically including rolling stock except rolling stock at current New York costs is $80 million.

Contingency

The soft costs include a federally mandated 40% contingency. The FTA mandates excessive contingencies – the norm in low-cost countries is 10-20%, and anything more than that is just wasted. The contingency figure varies by phase of design and decreases as it advances, but in the earliest phase it is 40%, and it’s in that phase that budgeting is done. However, 40% is only required over hard costs based on standardized cost categories (SCCs), and not over past ex post costs that incorporated contingency themselves. In effect, the estimation method the MTA and AECOM prefer bakes in a 40% overrun at each stage, letting project delivery get worse over time as the globalized system of procurement takes deeper roots in New York.

Overdesign and overbuilding

Based on our recommendations, the MTA shrank the station overages in Second Avenue Subway Phase 2. Phase 1 had station digs 100% longer than the platforms, based on standards that were both extravagant to the taxpayer and spartan to the end user – the extra space is not usable by passengers but instead for unnecessary break rooms, separated by department. By Phase 2, this was reduced to a 50% overage, and we hoped that proactive design around best practices would reduce this further.

Unfortunately, the overages are still substantial, 50% at St. Nicholas and 25% at the other two stations (Italy, Sweden, France, Germany, China: 3-20%). Moreover, the stations still have full-length mezzanines. This a longstanding New York tradition, going back to the 1930s with the opening of the IND lines starting with the A on Eighth Avenue in 1933. And like all other New York subway building traditions that conflict with how things are done in more advanced, non-English speaking countries, it belongs in the ashbin of history. Mined stations’ costs are sensitive to dig volume, and there is little need for such additional circulation space, for passenger comfort or fire safety. Mezzanines are essentially free if the stations are built cut-and-cover, in which case they are used for back-of-the-house space in advanced countries, but not if the stations are mined, in which case the best place for break rooms is under stairs and escalators.

Moreover, as we will explain soon at the Effective Transit Alliance, mined stations and bored tunnel require a minimum spacing from the street and from other tunnels – but the proposal includes much more space than necessary, forcing the stations to be deeper, more expensive, and less convenient as it takes a full five minutes to transfer between platforms or to get from the platform to the street. It’s possible to ge even shallower with shoring techniques used in China to reduce tunnel and station depth in complex urban undergrounds.

Proactive and reactive cost control

When the MTA announced cost savings and station size shrinkage in Phase 2, we were excited. But on hindsight, costs in effect fell from $7 billion to $7 billion. The savings were entirely reactive, designed to limit further cost overruns, and are not proactively incorporated into further projects.

No doubt, if a $7.7 billion project is approved against any honest benefit-cost analysis (which is not required in American law), then shrinkage in station footprint and reduction in mezzanine length will be found to be saving money in 2032, and the successor of Lieber, hired from the same pipeline of people whose takes on other countries are “I had a kid who did a semester abroad in Stockholm,” will be proud of reducing costs from $7.7 billion to $7.7 billion.

The path forward must instead incorporate cost savings proactively. There’s a way of building subway stations cost-effectively, and instead of quarter-measures, the MTA should adopt it; we have blueprints from a growing selection of examples, all in places that have avoided the destruction of subway building capacity infecting the entire English-dominant world in the last 25 years. The MTA can even hire people with direct transport official-to-transport official communication with peers at other agencies (for example, through COMET) and with the language skills to read documents produced in lower-cost countries, instead of people whose best skill is giving interviews to softball interviewers and talking about sports.